liminal | ˈlimənəl | adjective technical

1 occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold: I was in the liminal space between past and present | the paintings in this exhibition are the result of recent investigation into liminal states.

2 relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process: that liminal period when a child is old enough to begin following basic rules but is still too young to do so consistently.

DERIVATIVES liminality | ˌliməˈnalədē, -ˈnalitē | noun

ORIGIN late 19th century: from Latin limen, limin- ‘threshold’ + -al.

This will be a series of posts all about the above idea. There seems to be a lot written about this concept recently and liminality has become somewhat of a meme in and of itself. I’m curious to unpack this and also refer to a few things that might be examples of it within contemporary books/film/art/etc.

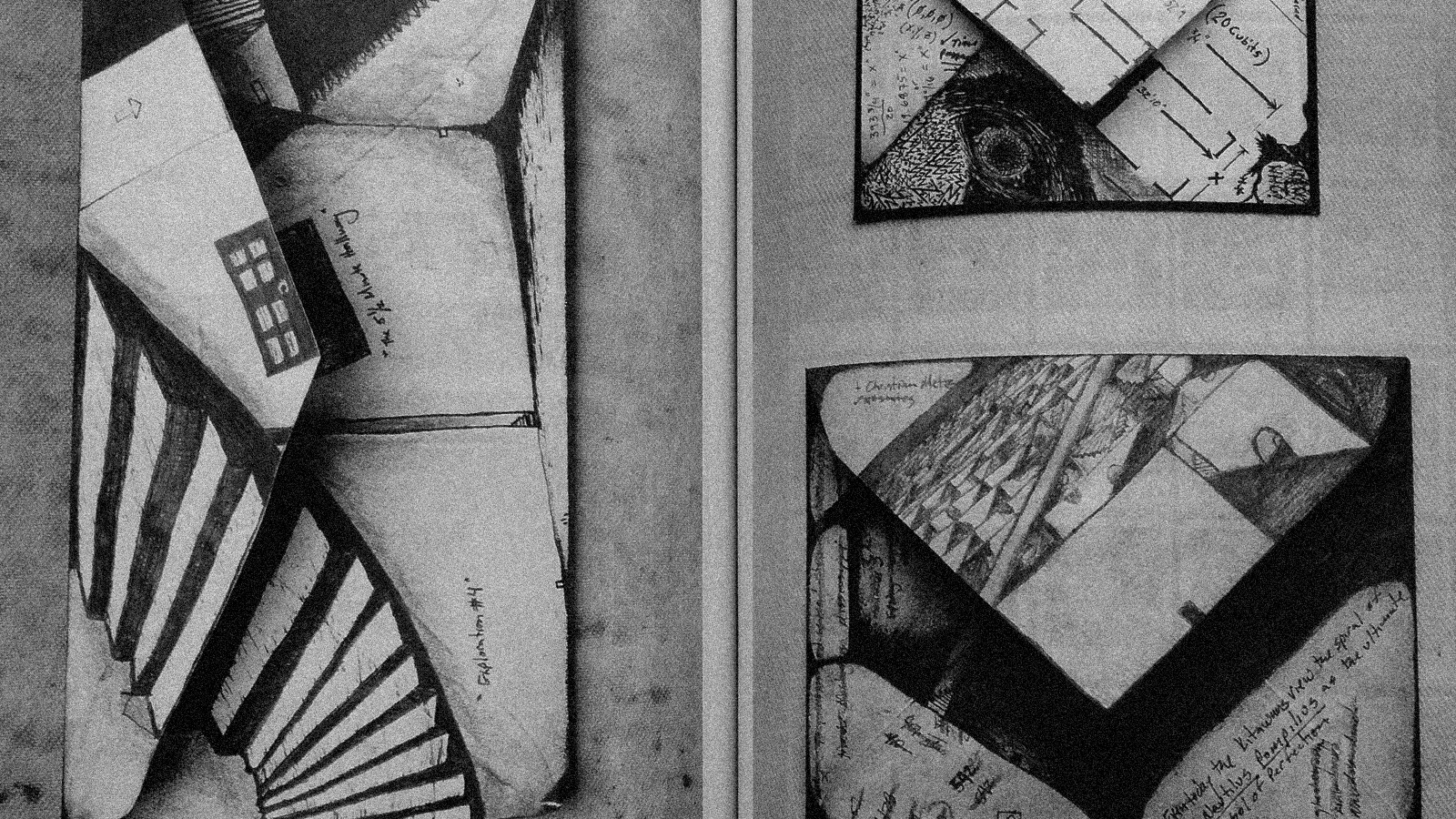

The first time I read House of Leaves (2000) was in high school, in the early 2000s. I can’t remember how I heard of the book, but I do remember getting instantly hooked. Danielewski’s novel (among other things) is about the Navidson family. Specifically about their house in Virginia. Doors begin appearing inside of the house, leading to rooms and hallways, and eventually to a spiral staircase. These new interiors break the laws of conventional physics; it’s not as though the house gets bigger from the outside. These interior spaces keep appearing, they keep growing. These emergent spaces are utterly featureless. They have smooth, grey walls, floors, and ceilings. There’s silence, save for a periodic low growl. The book stuck with me for a variety of reasons, the most resonant of which being the image of this sprawling non-place growing inside this house. There was ultimately no discoverable purpose or endpoint of this emergent place. It just kept growing and growing.

Anthropologist Marc Augé, in his 1995 essay and book Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, coined the phrase “non-place” to describe places where history, identity, and social relations are erased. Hotels, airports, and markets are all spaces he used as examples. He elaborated that they are marked by transience (people are there impermanently—save the staff, but that’s another matter), and people are there anonymously. Also, social and interpersonal interactions are minimized or absent altogether.

Augé continues that supermodernity—his term for our accelerated world (though if he thought the 1990s were fast…)—is especially apt at producing these kinds of spaces. In large part because technology, globalism, mass movement, among other factors, fragment our sense of belonging and identity while speeding us up in our movement through the world.

Of course, nuances abound. These non-places are often contested, hybridized spaces. Subjective experience plays a large part in how you view a place (maybe there’s an emotional resonance you feel towards a specific airport lounge?), and these non-places can also transform into places given the formation of (micro)communities within them.

We can also look to Mark Fisher’s idea of non-time as a complement to a non-place. For Fisher, in works like Capitalist Realism (2009), culture has come to a point of temporal stagnation. There are a few reasons for and characteristics of this:

- The future no longer feels imaginable. A good example is how movies from the 1980s were replete with futuristic utopias and dystopias. It’s hard to find many mainstream movies that imagine, say, the year 2100 (for better or worse).

- Fisher also writes that we are in a perpetual present. Things are sterile, repetitive. Our pop culture is full of nostalgia and retro-aesthetics. (A lot to unpack and nuance, but let’s roll with this.)

- At its most extreme, Fisher writes that culture might have frozen or even stalled out.

We can think of non-places as detaching us from space (space that’s full of cultural and historical resonances), and we can think of non-time as detaching us from progress—that is, the cultural or ideological energy that drives us toward a goal.

For Augé, non-places make us anonymous bodies in transit. For Fisher, non-time makes us ghosts of unrealized futures. We’re suspended in space and time, nothing is fully real or ours, and there’s no destination we’ll ever arrive to.